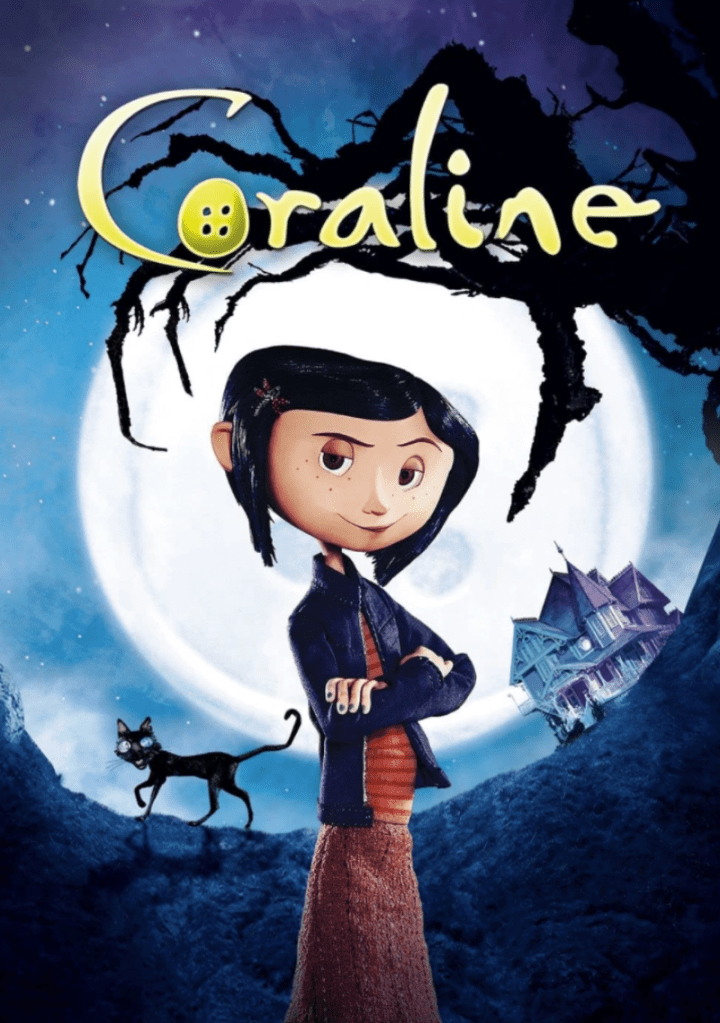

Everyone has a film that they turn to in specific moments of their life—a film that evokes nostalgia, reminds them of what once was and what could be. Moments of cinema that inspire and allow escapism to take precedence for just a few hours. For some, that film is Henry Selick’s 2009 masterpiece, Coraline. As a dark, fantasy horror film teetering between a whimsical, fantastical world and a grueling, unremarkable reality, Coraline highlights the modern-day horrors of childhood neglect and the mundanity of adolescence.

From the mind of Neil Gaiman comes a modern take on the female hero’s journey. Upon moving to a new state, Coraline Jones, a curious and adventurous young girl discovers a tiny hidden door in her new home that leads to an alternate reality. In this parallel world, everything seems perfect. With an “Other” mother who cooks elaborate meals and hand-sews stylish outfits, a father that sings clever little songs and has a magnificent, lifelike garden, and thoroughly entertaining neighbors, Coraline has no desire to wake up from this dream. But it’s not a dream, and everything is not what it seems. She soon realizes the sinister truth behind the Other World and must face the dark reality of her unravelling fantasy. Coraline must summon the courage to save her family while navigating the complexities of self-discovery, bravery, and the consequences of her own desire.

Diving head first into this uncanny dream, anyone with an eye for cinema will recognize that Coraline is a masterclass in worldbuilding. The contrasts between the real world and the Other World are noticeably incongruent both aesthetically and emotionally. Set in the spring of Ashland, Oregon, the film displays a drab, gray, and rainy atmosphere, devoid of color and riddled with formal structure. From the perfectly scalloped border of the rectangular burnt-orange background in the opening credits to the barren trees that stick straight up with spine-adjusting rigidity, no stone was left unturned when it came to establishing just how static and unyielding Coraline’s life has become since moving to the Pink Palace Apartments. This is evident on Coraline’s first visit to the Other World. Upon opening the hidden door, she is met with an accordion-like tunnel that expands by the second, pulsating with vibrant hues of cobalt and amethyst. This is the first splash of color the audience is introduced to outside of her bright yellow raincoat and electric blue asymmetrical bob.

Experiencing the tunnel for the first time evokes emotions in her that the viewer has not yet seen: confusion, followed by bewilderment and disbelief, and finally, what could only be described as curious determination. Once Coraline enters the other world, everything is highly saturated, intensely imaginative, and all that an 11-year old would be fascinated by. Throughout the film, the protagonist has many visceral reactions to vibrant colors and hues. Since this is a stop-motion picture with more than 15,000 hand-sanded and painted faces for all of the characters and over 6,300 face replacements for Coraline alone, each emotion and reaction displayed is not a coincidence. Her relationship to color and variety is reflected through these subtleties, and the filmmakers worked tirelessly to ensure that these nuances were translated nonverbally.

Moments throughout the film that further reinforce the disparity between Coraline and the reality she resides in. One such moment is when her real mother takes her shopping for school uniforms. Coraline picks up the only article of clothing that is not a shade of muted gray—a dynamic pair of lime green and orange gloves. She is immediately shut down by her mother who refuses to purchase them for her. Upon first viewing, the scene may not appear significant, but considering the fact that when Coraline begs for the gloves and her mother says no, she responds with, “My other mother would get them for me,” to which her mother retorts, “Maybe she should buy all your clothes” we begin to understand its impact. This line, facetiously delivered by Teri Hatcher, largely contributes to what makes this film relevant to audiences of all ages. Despite knowing that her parents are unemployed and their career endeavors leave her subject to neglect and isolation, she picks up the most expensive gloves in the sale pile— $24.99—and subconsciously triggers her mother’s maternal and financial insecurity. This scene is the final blow to Coraline’s relationship with her real mom. Not only does the Other Mother provide Coraline with new clothes during her next visit, but since her true form is a spider seamstress with needles for appendages, she handmakes—-no pun intended—a new outfit for Coraline, a vibrant blue sweater with sparkly white stars. From a character development perspective, this validates Coraline’s childlike wonder, making her feel seen in her style choices, but also solidifying the maternal bond Coraline desperately craves.

The beast that is stop-motion animation takes a keen eye and a strong sense of patience to accomplish. After Henry Selick received an early version of the story from Neil Gaiman in 2000, prior to the novel’s official release in 2002, “Coraline” underwent over four years of production, including 18 months of pre-production and two years of principal photography before hitting theaters. The 35 animators that contributed to the film were averaging 2.22 to 6.52 seconds of footage per week. Under the visionary direction of Henry Selick, renowned for The Nightmare Before Christmas, the film was released to audiences in February 2009. During this groundbreaking production, LAIKA Studios emerged as pioneers in the use of 3D-printed facial replacements.

The attention to detail in the film plays a large role in character development. For Mr. Bobinsky, Coraline’s neighbor and eccentric Russian ringleader of a jumping mouse circus, played by Ian McShane, the details seem boundless. His stature is rat-like as he is tall and has a noticeably large gut. Bobinsky has an extremely long wiry black mustache, closely resembling whiskers and his beady eyes sit slightly above his long rat-like nose. Atop his stained and tattered A-shirt and short shorts, he proudly wears the medal of a Chernobyl liquidator, and although it is not explicitly stated in the film, one can infer that his pale skin which is blue, is due to nuclear radiation poisoning. Some of the other details pertaining to character personality and intention are less obvious, such as Coraline’s neighbors, Miss Spink and Forcible. These two superstitious lesbian actresses, whose lives center around their former careers and obsession with their Scottish terriers, act as the oracles who help guide Coraline on her hero’s journey. As this is a modern day hero story for young girls, she seeks advice from the most opinionated, independent women in the film.

The reason Coraline repeatedly returns to the other world lies not in its whimsical nature and its enhancements, but in the companionship and nurturing she craves and which she receives from her Other Mother and father. The most nourishment Coraline receives from her real mother comes in the form of a multivitamin. She is often cast aside and ignored by her parents which motivates her to seek out relationships from her other parents. Blinded by her desire to be loved, Coraline fails to notice the eerie nature of the parallel dimension. Initially put off by everyone having buttons for eyes, it isn’t until the Other Mother shares the rules of her world—that Coraline can only stay if she lets her sew buttons in her eyes—that Coraline comes to the realization that all that glitters isn’t gold. The lesson here is to be grateful for what you have, even if it feels like it’s not enough. As a child, one might side with Coraline as her distress is evident, but once grown and evolved, that same person will understand the complexities of being a parent in today’s society. The hair-raising soundtrack and score, composed by French composer Bruno Coulais, create harrowing moments throughout the film. Without the masterful use of sound design, accompanied by the subtle visual cues to help build tension, the horror aspect of the film would be disregarded. The clever utilization of a made-up language in the soundtrack contributes to the unfamiliarity of the unsettling atmosphere that Selick has crafted. When taking a deeper look at the film, one can find themselves just as enthralled by the whimsical landscape as the protagonist. The foreboding suspense feels like a true betrayal. With striking visuals, disconcerting melodies, eccentric characters, and an overall message that resonates with viewers of all ages, Coraline (2009) is a timeless piece that continues to inspire even 16 years after its initial release.